If somebody ever tells you that there is something better than little feet running after your bicycle so that little hands can pull the hair from your legs, you are talking to a liar my friend.

I love the children from my compound. I love how they shriek my name when they see me, I love how fist-pounding still hasn’t gotten old after three months and a half, and I love how genuinely excited they become for seemingly mundane things. Laundry by hand? An occasion to have soap all over their little faces! A plate on the ground? An incredible rolling toy that can be amusing for hours! A visit to the farm? A parade through the village and a game of bug catching! Everyday life? An incredible adventure…

Population boom is an issue in rural Ghana. Last year, only ten people died in my village but more than sixty were born. According to the Assembly Man, if you would visit each compound in the community, you would find at least one pregnant woman. People seem to be aware of contraceptive measures, but it is believed that labour is needed on the farm and polygamous relationships lead to many children. Many, many little feet to run after bicycles but also many, many little mouths to feed, little minds to educate, and little hands to fist-pound.

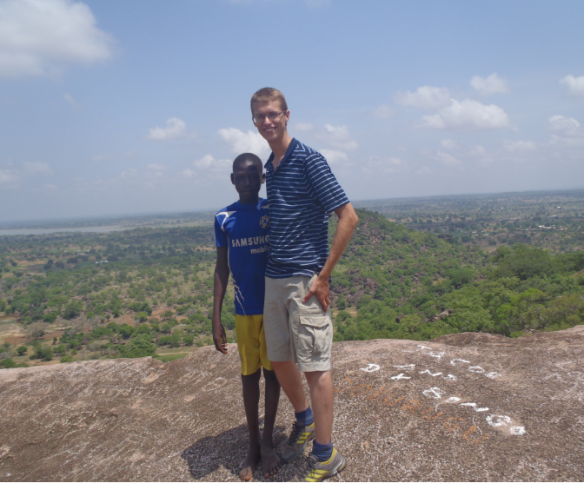

A few nights ago, I was sitting on my favourite wooden bench with the straw roof close to my house with a few of my fellow Dagban men. I was proudly told that about thirty years ago, my landlord could come home with three antelopes after a day of hunting. I listened and learnt about the days when the forest surrounded the village and the neighbouring farms. The days when lions and wild game roamed were painted beautifully for me with the few shared words we hold dear.

When I went to the farm this weekend, a small boy caught a flying bird with his skills and slingshot. This is the extent of the hunting possible today. Many, many small mouths had eaten all of the wild animals.

In my three months and a half here, I’ve noticed some of the little hands grow bigger and bigger. Soon, these hands will start looking for seeds and land to start feeding their own families. Soon, they’ll be having their own little ones. Soon, the days when land was available to farm might be told sitting on the bench at night at the same time as the story about the antelopes.

The world is changing. Farming is turning chemical, yields and pollution are both increasing. The youth is slowly getting educated and there is a mass exodus to the cities. Land might not be the issue, but without proper planning, unforeseen consequences, like the disappearance of the antelope could certainly happen.

The world is changing, but laundry should always be a game and it should always be possible to transform a plate into the most wonderful toy. Soon, I’ll be changing the way I live drastically, and moving halfway across the world. I’ve spent three months and a half, to have more questions than I had before starting. Hopefully I’ll remember the answer to one key question though, as answered without uttering a word from the wisest of them all.

Everyday life? An incredible adventure…